If Medo's name sounds familiar, it's because in 1999 she founded Prolacta, which became the first for-profit company in the US to produce human milk-derived products. Medo, who left Prolacta under a bit of a cloud, doesn't appear to have sold much, if any, of her new company's milk products. I've been unable to find a single hospital in the US that has purchased her product, and I've been unable to find anyone who has received Medolac's milk.

What's she doing with all that milk?

Stockpiling is an age-old tactic that in a free market can artificially create a shortage, raising prices. It's also a good way to swipe contracts out from under a competitor known to sign exclusive contracts with hospitals. Medo could flood the market overnight which could have the effect of lowering prices and jamming up the freezers of Prolacta, described by Medo as her only global competitor, stretching their financial resources as they recalibrate to try to continue operating with lower pricing.

Or, maybe she has another plan for the milk. Medo says Medolac "stands ready to work with government and relief efforts." Back in 2010 the earthquake in Haiti generated a literal outpouring of support from breastfeeding moms in the US who were encouraged by the International Milk Bank Project (IMBP) to donate milk to save babies in Haiti.

Because if you're going to make a profit, it's all about supply and demand. In "The Startup Game," venture capitalist and early Prolacta funder Bill Draper talks about how Medo's company struggled in the early days to secure supply. News outlets and bloggers at the time criticized Medo's deal with the IMBP to divert milk given by moms who thought it was being sent to Africa for AIDS orphans. Draper says supply remained a concern until they set up a system through an affiliate, Two Maids a Milkin' "with an appropriate incentive program."

Prolacta was also criticized over Two Maids, which went on to be the "National Milk Bank." Up until this time, all milk banks in the US were non-profit, and there was nothing to distinguish these new "milk banks" from legit local efforts to collect breastmilk for babies in their own communities whose mothers couldn't produce enough. Prolacta was seen to be profiting on the backs of donor moms who didn't always know the milk they provided for free to save babies, was lining the pockets of investors along the way.

|

| Amy West is one of several bloggers who took on the issue of Prolacta's deceptive tactics. Read her blog here. |

The newspaper reporting Medolac's million dollar payout to moms is in Utah, which is where Prolacta went a few years ago in an effort to secure more supply. Utah has one of the highest rates of breastfeeding initiation and duration in the country – ripe grounds for donor picking. (Human Milk News, 2011, Denver Mothers' Milk Bank, Prolacta vie for Utah #humanmilk donations)

Prolacta continues and has moved to set up supply deals directly with hospitals. It started a few years ago with the Texas Children's Hospital - all milk donated by moms to the hospital goes to Prolacta, and the hospital provides Prolacta products back for its patients. No-one knows the percentage of Texas moms' milk that actually went to help treat Texas babies at Texas Children's, but Prolacta said in August 2013 they had received 55,564 ounces through their Texas Children's donations.*(See update below.) By comparison, the non-profit milk bank in Austin distributed 425,000 ounces of milk in 2013, and North Texas's non-profit milk bank distributed 414,618 in the same period. This means over 5 per cent of the moms with milk to give in Texas were diverted to Texas Children's to provide their milk for free to a for-profit collection scheme instead of giving that milk to their state's non-profit milk banks.

That experiment must have been profitable because Prolacta also started a program for other hospitals to:

"...recruit mothers within the community who have extra breast milk and who want to help make a difference. In turn, Prolacta makes the process simple for participating hospitals by managing the breast milk donor qualification process."

It's described as turn-key with $0 investment. Why is Prolacta so anxious to work directly with hospitals? Well, of course, that's where the breastfeeding moms - the suppliers of the raw product - begin their lactation journey. And in a free market, it's all about securing supply.

The human milk marketplace in the US, however, is far from being a free market.

There are gatekeepers and regulatory pressures controlling the use of human milk in hospitals in the US. Only a handful of states that regulate milk banks (California, Maryland, New York and Texas – with New Jersey considering legislation) Even fewer regulate purchase or sale of human milk. There are still big hurdles to the distribution of human milk products. It's hard to convince neonatologists – and experts who develop protocols for sick babies – to accept new human-milk products.

The caution stems from the AIDS crisis of the 80s which shut down human milk banks overnight. Since then, despite pasteurization and strict screening protocols – modelled after those in place at blood banks – it has taken decades to regain trust in the safety of donor human milk. The situation is further complicated by competition from infant formula companies whose bottom line is enhanced by expensive, specialized products, and which operate in an environment with little regulation of product quality and marketing. Trust in infant formula products is secured with expensive marketing campaigns disguised as educational seminars that use industry-funded research to sell the benefits of one concoction over another. It's in a formula company's best interests to erode both medical practitioner and public confidence in donor human milk as it competes directly with their products.

The free market is even further fettered by the existence of our pesky network of non-profit milk banks that undermine profit-taking by providing processed milk for a fee that simply covers costs, and relies on moms to freely give milk. Prolacta and Medolac are in direct competition with non-profit milk banks for access to these generous moms for their extra milk. For years Prolacta rode the wave of altruism, with its "milk bank" fronts like the National Milk Bank that at first outright duped women who thought they were donating to a non-profit, and then later through the forging of sponsorship deals with charities. (See Human Milk News Aug 2012: U.S. company Prolacta milks donors, charity partners)

|

| From Two Maids Milkin'/National Milk Bank |

Medo clearly understands the need to secure supply and her move to pay mothers directly has been successful enough to force Prolacta to also pay moms to keep from losing them (See Human Milk News June, 2014 Prolacta now paying $1/ounce for breast milk.) It's only a shift in tactics, though, as the incentives were already costing Prolacta about the same amount per ounce.

Meanwhile, Medolac is trying new tactics. One big one is targeting the cream of the crop of milk

|

| The milk stash of Stephanie Santiago, who built this stash todonate to a friend who was adopting. (Used with permission) |

It is impossible to tell if the amount of local milk donated is reciprocated by processed milk flowing back to the community for babies in need. Non-profits provide donor milk across the nation even though not every hospital or state has a collection depot or milk bank. There are lots of questions about equity and for-profits complicate the situation. Prolacta's most lucrative product concentrates many ounces of milk to provide a human-milk-derived nutritional supplement for the very smallest, sickest babies. This product replaces a bovine-based supplement that most agree increases the risk of illness and death - but some wonder if it should be better regulated to prevent it from being overused. And Prolacta's use of infant formula company Abbott to market their products gives pause to many who are familiar with that company's unfettered and predatory marketing practices in both the US and around the world.

Medolac's other new tactic is a partnership with the Clinton Global Initiative to invite black mothers to sell their milk as a way of boosting black breastfeeding rates. Well-known author and black breastfeeding advocate Kimberly Seals Allers wrote about this for the New York Times parenting blog Motherlode, noting none of the Medolac's product made with milk purchased from black Detroit mothers would be sold back to hospitals serving the black babies of Detroit. I urge you to take a moment here to read Seals Allers' post, and if you're not familiar with how outrageously undermined black breastfeeding mothers are in Detroit, read this too.

Medolac's move into Detroit has been met with a lot of head-scratching, and I have to wonder what Medo is up to. Seals Allers says "these are problems that could best be addressed by women living and working in the community" but I can see Medo considering that publicity about the needs of premature black babies in Detroit could drive yet more offers of milk from sympathetic, breastfeeding mothers in the way they responded to Haiti and the AIDS orphans of South Africa.

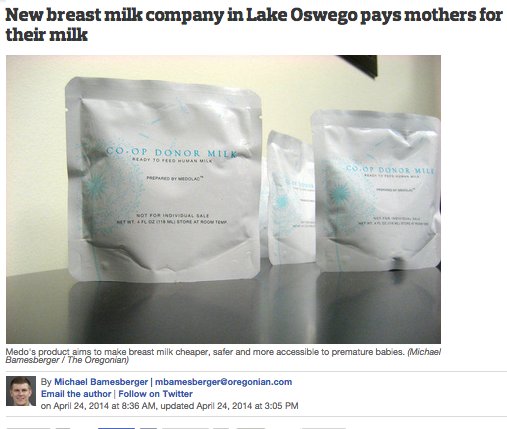

Medolac's 1 million ounce stockpile remains a mystery. How many US babies in need went without donor human milk in 2013 because moms were convinced to sell their milk to Medolac? The marketing has been slick and it's clear Medo has learned from past Prolacta mistakes. Instead of a for-profit, her supply-side sister company is structured as a cooperative, promising moms they can save babies, earn money, and even "shape the future of of milk banking." It's clear milk is pouring into Medo's Oregon factory and even though moms are referred to as donors, it's becoming obvious that the moms who are paid to provide milk don't seem to have the same incentive to ask what's being done with it.

Medolac's 1 million ounce stockpile remains a mystery. How many US babies in need went without donor human milk in 2013 because moms were convinced to sell their milk to Medolac? The marketing has been slick and it's clear Medo has learned from past Prolacta mistakes. Instead of a for-profit, her supply-side sister company is structured as a cooperative, promising moms they can save babies, earn money, and even "shape the future of of milk banking." It's clear milk is pouring into Medo's Oregon factory and even though moms are referred to as donors, it's becoming obvious that the moms who are paid to provide milk don't seem to have the same incentive to ask what's being done with it.We'll never know for sure how many babies lost out because of Medolac's stockpiling over the last 18 months. Some of these moms may have otherwise donated to non-profit milk banks, or informally, through milksharing networks or to friends or neighbours, instead of selling it. Or that milk may simply have gone down the drain. Or perhaps the super-producers simply wouldn't have made as much milk without the incentive to sell it. Despite concerns expressed by HMBANA's milk banks about a shortage of donor milk, there are indications the problem is not a lack of milk, but confusion about why, where and how to donate. Milksharing advocates have been saying for years human milk is not a scarce commodity, but rather "a free-flowing resource and we are dumping it down the drain." Lately Prolacta has been echoing that claim. Well-known blogger Annie PhDinParenting has suggested the problem is that milk is a commodity that doesn't have an advanced distribution channel.

Medo says she wants to change all this. Her pitch is to "Increase the Global Supply and Affordability of Donor Milk" through her "radically different" approach relying on "economies of scale" and "novel solutions...that close the gap between supply and demand."

Medo says she wants to change all this. Her pitch is to "Increase the Global Supply and Affordability of Donor Milk" through her "radically different" approach relying on "economies of scale" and "novel solutions...that close the gap between supply and demand."Medolac has diverted 1 million ounces of human milk away from sick and needy babies by convincing moms they are doing a good thing by selling their milk to a "cooperative"... that believes "mothers should shape the future of milk banking" by participating in "the only paid donation program in the United States."

If a non-profit community milk bank took in a million ounces of milk without disbursing it there would be a huge outcry. And yet, Medolac and its sister company won't say a word about how or where their stockpile will be used.

It's completely unclear who – other than the profit takers – will benefit. What is clear that the milk moms produce for Medolac is not going to sick and needy babies in their communities.

If you have milk to donate, consider contacting a non-profit HMBANA milk bank operating in your community. HMBANA provides milk across the US and Canada and works with teams of volunteers to open new milk banks in cities where there are none. If you can't donate to a milk bank or want your milk to go to families who can't receive milk from milk banks, contact your local milksharing organization.

*Update Dec 8, 2013: On the question of how much milk donated to Texas Children's Hospital's Prolacta milk bank remains in Texas - a TCH video "Spotlight on on Donor Milk Program," released in the same week as a August 2013 Prolacta news release that says Texas Children's diverted 55,000 oz to Prolacta, quotes Nancy Hurst of Texas Children's saying they use "about 3,000 ounces a month." That is about 36,000 ounces per year. So about 35 per cent or almost 20,000 ounces of milk donated to by Houston-area moms is either leaving the state, or is being used for another purpose according to TCH.

No comments:

Post a Comment